THE AIRLINE PILOTS FORUM & RESOURCE

Contaminated Aircraft Air and Emergency Checklist |

| Source: Aviation Contaminated Air Reference Manual |

|

| Emergency Checklists and Initial Crew Responses © | |

| by Susan Michaelis | |

As an airline pilot, when faced with an aircraft system malfunction or problem, it is necessary to carry out certain set down procedures as laid down in the emergency checklist. These emergency checks will usually be written down in a printed emergency checklist of which there will be two duplicate copies. One easily accessible to each pilot. The emergency checks will be unique to the specific model of aircraft. Some aircraft types also have electronic checklists which are displayed on electronic flight screens and these will show the pilots the appropriate checklist for the specific problem. All aircraft malfunctions are dealt with by actioning the emergency checklist very methodically. Extremely important problems which are time critical, such as an engine fire, will also have some ‘memory items’, that is to say tasks which the pilots must carry out by memory in time critical situations, before referring to the checklist. Once pilots have completed the memory items, they would, at a suitable time, action the remaining part of the emergency checklist, check they had carried out the memory items correctly and then do the other items applicable to the malfunction, step by step, from the checklist. In carrying out both memory items and items from the emergency checklist, crews are trained to do nothing without each pilot confirming that the action about to be taken by the other pilot is correct, before it is actioned.

At this point it’s worth outlining to those of you not familiar with the workings of an airline cockpit that today most commercial aircraft only have two pilots due to advances in automation of aircraft systems. One pilot will be the Captain and the other pilot the co-pilot, referred to in some countries as the First Officer. Both pilots will usually have the same industry recognised qualifications known as an Airline Transport Pilots Licence (ATPL) or Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) which is the highest qualification in the industry. The Captain will normally be the more senior and experienced from within that particular airline. A Captain like a ship Captain can be identified by the 4 stripes on their jacket or on their shirt epaulettes. Many passengers believe the Captain is the pilot and the co-pilot is the back up pilot or radio person, however this is not the case. Both are fully qualified to fly the aircraft and usually take turns to fly the aircraft whilst the other pilot does the radio and the other non flying duties. Usually, the pilot flying the aircraft is known as the Handling Pilot and the other pilot will be the Non Handling Pilot with clearly defined roles and tasks to complete. The important point being that both pilots are fully trained and qualified to do the job. The copilot could quite easily have been a captain in the past on a different aircraft type or with another airline. The Captain has the overall responsibility for the aircraft, crew and passengers on board.

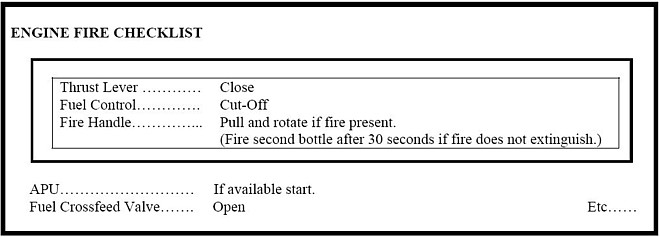

Returning to the checklists and the memory items mentioned above, we will now have a closer look at how these work, as this issue is an important part in the debate to come. A generic emergency checklist for an aircraft engine fire is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Generic Engine Fire Checklist

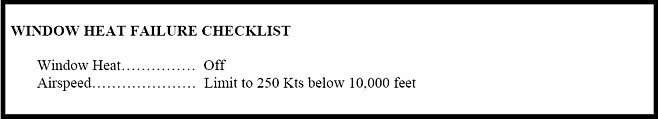

The inner box within the checklist represents the memory items that the pilot will do initially without the checklist. Once these items are completed and the moment is suitable, the non handling pilot will get out the checklist and complete all the items including confirmation that the memory items were completed. In the example above, the first memory item is: Thrust Lever – Close. Checklists which have no memory items do not have an inner box such as the checklist for, say, a failed window heater shown in Figure 2:

Checklists play an important part in the contaminated air story and to understand their significance it is necessary to go back to the 1970s and 1980s. This is because the emphasis of the checklists relating to contaminated air has only in very recent times been changed. These recent changes to some of the emergency checklists have on the outside appeared to show an industry that takes contaminated air events seriously; however, as will be discovered shortly, the problem is still not adequately addressed as crews have yet to be properly educated and many of the facts surrounding the issue are still denied.

Figure 2: Window Heat Failure

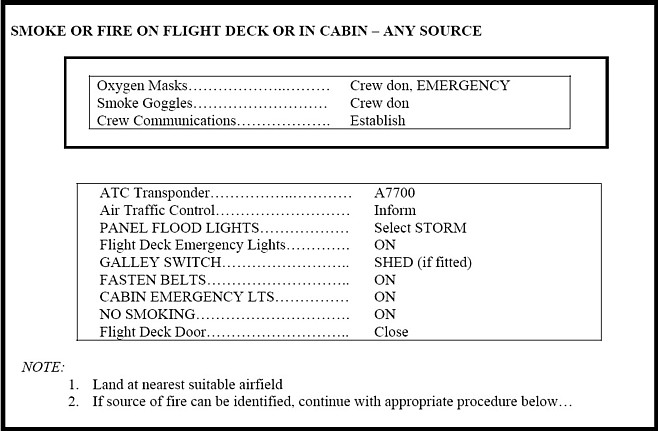

The emergency checklists that contain references to the area of concern previously had the heading, ‘Smoke or Fire’ before better guidance was given on contaminated air. In those early days, most commercial passenger jet aircraft checklists were like the British Aerospace BAe 146 checklist example shown in Figure 3 [29] and fell well short in providing the guidance needed for crews:

Figure 3: BAe 146. Smoke Or Fire On Flight Deck Checklist pre 2001

Very clearly the checklist says SMOKE or FIRE, yet there is no mention of ‘contaminated air‘ or ‘fumes’. This was because the industry did not take contaminated air seriously and pilots were not trained to act in a contaminated air situation. Some in the airline industry have more recently said that smoke covers fumes, however, this cannot be the case as smoke is visible while fumes in lay terms are not visible. Additionally, every normal and abnormal potential action required by pilots is covered in the aircraft manuals and checklists and the issue of non visible fumes was never previously considered, otherwise it would have been addressed just like all other potential events. The lack of specific guidance in the emergency checklists, combined with an aviation industry telling crews contaminated air was safe saw, and still sees, many airline pilots not taking contaminated air events seriously. Pilots misled by a lack of education and proper guidance. These pilots have not viewed contaminated air or fumes as an aircraft defect and have got used to being exposed to contaminated air, assuming that this is not a health and flight safety issue. These factors coupled by the fact that such events were not listed in the pilot required actions covered in the emergency and abnormal procedures checklists, has led to a situation where the first memory item in the emergency checklist which calls for pilots to use emergency oxygen (see figure 3) was never actioned. Pilots who experienced contaminated air events which had no smoke or fire were misled into dealing with contaminated air as if it had no risk to health or flight safety. They acted like the millions of people who dealt with smoking before the facts came out that smoking was not good for you. There is a great similarity between smoking and contaminated air exposures. Both industries knew what the effects could be as you will discover within this book, but grossly failed to take steps to address the issue.

Flight Safety Aspects of Contaminated Air

You are reading >> Emergency Checklists and Initial Crew Responses

Reporting Contaminated Air Events with Samples of Known Events

FODCOM (Flight Operations Department Communication) number 17/2000

FODCOM (Flight Operations Department Communication) number 14/2001 and 21/2002

Aviation Regulators Misinterpret Main Ventilation Airworthiness / Safety Standard

References

29. BAe (1990) BAe 146 Manufacturer’s Operations Manual: Emergency and Abnormal Procedures Check List/Smoke or Fire Protection. British Aerospace Systems, Hatfield.